Phylogenetic Comparative Methods learning from trees

- Chapter 6: Beyond Brownian Motion

- Section 6.1: Introduction

- Section 6.2: Transforming the evolutionary variance-covariance matrix

- Section 6.3: Variation in rates of trait evolution across clades

- Section 6.4: Non-Brownian evolution under stabilizing selection

- Section 6.6: Early burst models

- Section 6.7: Peak shift models

- Section 6.8: Summary

- Section 6.9: Footnotes

- Section 6.10: Appendix: Deriving an OU model under stabilizing selection

Chapter 6: Beyond Brownian Motion

Section 6.1: Introduction

Detailed studies of contemporary evolution have revealed a rich variety of processes that influence how traits evolve through time. Consider the famous studies of Darwin’s finches, Geospiza, in the Galapagos islands carried out by Peter and Rosemary Grant, among others (e.g. Grant and Grant 2011). These studies have documented the action of natural selection on traits from one generation to the next. One can see very clearly how changes in climate – especially the amount of rainfall – affect the availability of different types of seeds (Grant and Grant 2002). These changing resources in turn affect which individuals survive within the population. When natural selection acts on traits that can be inherited from parents to offspring, those traits evolve.

One can obtain a dataset of morphological traits, including measurements of body and beak size and shape, along with a phylogenetic tree for several species of Darwin’s finches. Imagine that you have the goal of analyzing the tempo and mode of morphological evolution across these species of finch. We can start by fitting a Brownian motion model to these data. However, a Brownian model (which, as we learned in Chapter 3, corresponds to a few simple scenarios of trait evolution) hardly seems realistic for a group of finches known to be under strong and predictable directional selection.

Brownian motion is very commonly used in comparative biology: in fact, a large number of comparative methods that researchers use for continuous traits assumes that traits evolve under a Brownian motion model. The scope of other models beyond Brownian motion that we can use to model continuous trait data on trees is somewhat limited. However, more and more methods are being developed that break free of this limitation, moving the field beyond Brownian motion. In this chapter I will discuss these approaches and what they can tell us about evolution. I will also describe how moving beyond Brownian motion can point the way forward for statistical comparative methods.

In this chapter, I will consider four ways that comparative methods can move beyond simple Brownian motion models: by transforming the variance-covariance matrix describing trait covariation among species, by incorporating variation in rates of evolution, by accounting for evolutionary constraints, and by modeling adaptive radiation and ecological opportunity. It should be apparent that the models listed here do not span the complete range of possibilities, and so my list is not meant to be comprehensive. Instead, I hope that readers will view these as examples, and that future researchers will add to this list and enrich the set of models that we can fit to comparative data.

Section 6.2: Transforming the evolutionary variance-covariance matrix

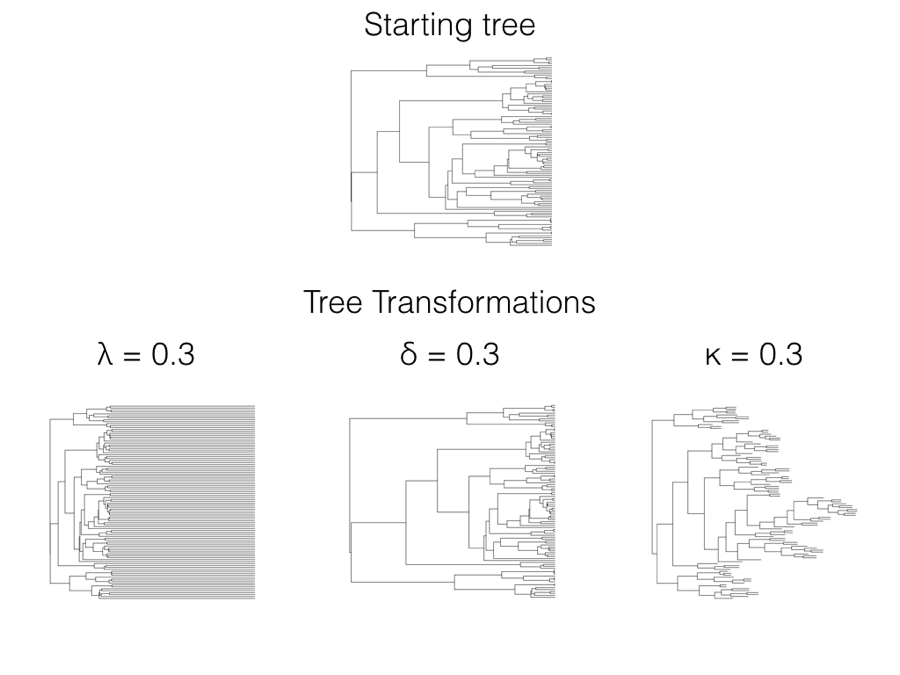

In 1999, Mark Pagel introduced three statistical models that allow one to test whether data deviates from a constant-rate process evolving on a phylogenetic tree (Pagel 1999a,b)1. Each of these three models is a statistical transformation of the elements of the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix, C, that we first encountered in Chapter 3. All three can also be thought of as a transformation of the branch lengths of the tree, which adds a more intuitive understanding of the statistical properties of the tree transformations (Figure 6.1). We can transform the tree and then simulate characters under a Brownian motion model on the transformed tree, generating very different patterns than if they had been simulated on the starting tree.

Figure 6.1. Branch length transformations effectively alter the relative rate of evolution on certain branches in the tree. If we make a branch longer, there is more “evolutionary time” for characters to change, and so we are effectively increasing the rate of evolution along that branch. Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

There are three Pagel tree transformations (lambda: λ, delta: δ, and kappa: κ). I will describe each of them along with common methods for fitting Pagel models under ML, AIC, and Bayesian frameworks. Pagel’s three transformations can also be related to evolutionary processes, although those relationships are sometimes vague compared to approaches based on explicit evolutionary models rather than tree transformations (see below for more comments on this distinction).

Perhaps the most commonly used Pagel tree transformation is λ. When using λ, one multiplies all off-diagonal elements in the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix by the value of λ, restricted to values of 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1. The diagonal elements remain unchanged. So, if the original matrix for r species is:

(Equation 6.1)

$$

\mathbf{C_o} =

\begin{bmatrix}

\sigma_1^2 & \sigma_{12} & \dots & \sigma_{1r}\\

\sigma_{21} & \sigma_2^2 & \dots & \sigma_{2r}\\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\

\sigma_{r1} & \sigma_{r2} & \dots & \sigma_{r}^2\\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Then the transformed matrix will be:

(Equation 6.2)

$$

\mathbf{C_\lambda} =

\begin{bmatrix}

\sigma_1^2 & \lambda \cdot \sigma_{12} & \dots & \lambda \cdot \sigma_{1r}\\

\lambda \cdot \sigma_{21} & \sigma_2^2 & \dots & \lambda \cdot \sigma_{2r}\\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\

\lambda \cdot \sigma_{r1} & \lambda \cdot \sigma_{r2} & \dots & \sigma_{r}^2\\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

In terms of branch length transformations, λ compresses internal branches while leaving the tip branches of the tree unaffected (Figure 6.1). λ can range from 1 (no transformation) to 0 (which results in a complete star phylogeny, with all tip branches equal in length and all internal branches of length 0). One can in principle use some values of λ greater than one on most variance-covariance matrices, although many values of λ > 1 result in matrices that are not valid variance-covariance matrices and/or do not correspond with any phylogenetic tree transformation. For this reason I recommend that λ be limited to values between 0 and 1.

λ is often used to measure the “phylogenetic signal” in comparative data. This makes intuitive sense, as λ scales the tree between a constant-rates model (λ = 1) to one where every species is statistically independent of every other species in the tree (λ = 0). Statistically, this can be very useful information. However, there is some danger is in attributing a statistical result – either phylogenetic signal or not – to any particular biological process. For example, phylogenetic signal is sometimes called a “phylogenetic constraint.” But one way to obtain a high phylogenetic signal (λ near 1) is to evolve traits under a Brownian motion model, which involves completely unconstrained character evolution. Likewise, a lack of phylogenetic signal – which might be called “low phylogenetic constraint” – results from an OU model with a high α parameter (see below), which is a model where trait evolution away from the optimal value is, in fact, highly constrained. Revell et al. (2008) show a broad range of circumstances that can lead to patterns of high or low phylogenetic signal, and caution against over-interpretation of results from analyses of phylogenetic signal, like Pagel’s λ. Also worth noting is that statistical estimates of λ under a ML model tend to be clustered near 0 and 1 regardless of the true value, and AIC model selection can tend to prefer models with λ ≠ 0 even when data is simulated under Brownian motion (Boettiger et al. 2012).

Pagel’s δ is designed to capture variation in rates of evolution through time. Under the δ transformation, all elements of the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix are raised to the power δ, assumed to be positive. So, if our original C matrix is given above (equation 6.1), then the δ-transformed version will be:

(Equation 6.3)

$$

\mathbf{C_\delta} =

\begin{bmatrix}

(\sigma_1^2)^\delta & (\sigma_{12})^\delta & \dots & (\sigma_{1r})^\delta\\

(\sigma_{21})^\delta & (\sigma_2^2)^\delta & \dots & (\sigma_{2r})^\delta\\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\

(\sigma_{r1})^\delta & (\sigma_{r2})^\delta & \dots & (\sigma_{r}^2)^\delta\\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Since these elements represent the heights of nodes in the phylogenetic tree, then δ can also be viewed as a transformation of phylogenetic node heights. When δ is one, the tree is unchanged and one still has a constant-rate Brownian motion process; when δ is less than 1, node heights are reduced, but deeper branches in the tree are reduced less than shallower branches (Figure 6.1). This effectively represents a model where the rate of evolution slows through time. By contrast, δ > 1 stretches the shallower branches in the tree more than the deep branches, mimicking a model where the rate of evolution speeds up through time. There is a close connection between the δ model, the ACDC model (Blomberg et al. 2003), and Harmon et al.’s (2010) early burst model [see also Uyeda and Harmon (2014), especially the appendix).

Finally, the κ transformation is sometimes used to capture patterns of “speciational” change in trees. In the κ model, one raises all of the branch lengths in the tree by the power κ (we require that κ ≥ 0). This has a complicated effect on the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix, as the effect that this transformation has on each covariance element depends on both the value of κ and the number of branches that extend from the root of the tree to the most recent common ancestor of each pair of species. So, if our original C matrix is given by equation 6.1, the transformed version will be:

(Equation 6.4)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mathbf{C_o} = \\

\left(\begin{smallmatrix}

b_{1,1}^k + b_{1,2}^k \dots + b_{1,d_1}^k &

b_{1-2,1}^k + b_{1-2,2}^k \dots + b_{1-2,d_{1-2}}^k &

\dots &

b_{1-r,1}^k + b_{1-r,2}^k \dots + b_{1-r,d_{1-r}}^k \\

b_{2-1,1}^k + b_{2-1,2}^k \dots + b_{2-1,d_{1-2}}^k &

b_{2,1}^k + b_{2,2}^k \dots + b_{2,d_2}^k &

\dots &

b_{2-r,1}^k + b_{2-r,2}^k \dots + b_{2-r,d_{2-r}}^k \\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\

b_{r-1,1}^k + b_{r-1,2}^k \dots + b_{r-1,d_{1-r}}^k &

b_{r-2,1}^k + b_{r-2,2}^k \dots + b_{r-2,d_{1-2}}^k &

\dots &

b_{r,1}^k + b_{r,2}^k \dots + b_{r,d_{r}}^k \\

\end{smallmatrix}\right) \\

\end{array}

$$

where bx, y is the branch length of the branch that is the most recent common ancestor of taxa x and y, while dx, y is the total number of branches that one encounters traversing the path from the root to the most recent common ancestor of the species pair specified by x, y (or to the tip x if just one taxon is specified). Needless to say, this transformation is easier to understand as a transformation of the tree branches themselves rather than of the associated variance-covariance matrix.

When the κ parameter is one, the tree is unchanged and one still has a constant-rate Brownian motion process; when κ = 0, all branch lengths are one. κ values in between these two extremes represent intermediates (Figure 6.1). κ is often interpreted in terms of a model where character change is more or less concentrated at speciation events. For this interpretation to be valid, we have to assume that the phylogenetic tree, as given, includes all (or even most) of the speciation events in the history of the clade. The problem with this assumption is that speciation events are almost certainly missing due to sampling: perhaps some living species from the clade have not been sampled, or species that are part of the clade have gone extinct before the present day and are thus not sampled. There are much better ways of estimating speciational models that can account for these issues in sampling (e.g. Bokma 2008; Goldberg and Igić 2012); these newer methods should be preferred over Pagel’s κ for testing for a speciational pattern in trait data.

There are two main ways to assess the fit of the three Pagel-style models to data. First, one can use ML to estimate parameters and likelihood ratio tests (or AICc scores) to compare the fit of various models. Each represents a three parameter model: one additional parameter added to the two parameters already needed to describe single-rate Brownian motion. As mentioned above, simulation studies suggest that this can sometimes lead to overconfidence, at least for the λ model. Sometimes researchers will compare the fit of a particular model (e.g. λ) with models where that parameter is fixed at its two extreme values (0 or 1; this is not possible with δ). Second, one can use Bayesian methods to estimate posterior distributions of parameter values, then inspect those distributions to see if they overlap with values of interest (say, 0 or 1).

We can apply these three Pagel models to the mammal body size data discussed in chapter 5, comparing the AICc scores for Brownian motion to that from the three transformations. We obtain the following results:

| Model | Parameter estimates | lnL | AICc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian motion | σ2 = 0.088, θ = 4.64 | -78.0 | 160.4 |

| lambda | σ2 = 0.085, θ = 4.64, λ = 1.0 | -78.0 | 162.6 |

| delta | σ2 = 0.063, θ = 4.60, δ = 1.5 | -77.7 | 162.0 |

| kappa | σ2 = 0.170, θ = 4.64, κ = 0.66 | -77.3 | 161.1 |

Note that Brownian motion is the preferred model with the lowest AICc score, but also that all four AICc scores are within 3 units – meaning that we cannot easily distinguish among them using our mammal data.

Section 6.3: Variation in rates of trait evolution across clades

One assumption of Brownian motion is that the rate of change (σ2) is constant, both through time and across lineages. However, some of the most interesting hypotheses in evolution relate to differences in the rates of character change across clades. For example, key innovations are evolutionary events that open up new areas of niche space to evolving clades (Hunter 1998; reviewed in Alfaro 2013). This new niche space is an ecological opportunity that can then be filled by newly evolved species (Yoder et al. 2010). If this were happening in a clade, we might expect that rates of trait evolution would be elevated following the acquisition of the key innovation (Yoder et al. 2010).

There are several methods that one can use to test for differences in the rate of evolution across clades. First, one can compare the magnitude of independent contrasts across clades; second, one can use model comparison approaches to compare the fit of single- and multiple-rate models to data on trees; and third, one can use a Bayesian approach combined with reversible-jump machinery to try to find the places on the tree where rate shifts have occurred. I will explain each of these methods in turn.

Section 6.3a: Rate tests using phylogenetic independent contrasts

One of the earliest methods developed to compare rates across clades is to compare the magnitude of independent contrasts calculated in each clade (e.g. Garland 1992). To do this, one first calculates standardized independent contrasts, separating those contrasts that are calculated within each clade of interest. As we noted in Chapter 5, these contrasts have arbitrary sign (positive or negative) but if they are squared, represent independent estimates of the Brownian motion rate parameter (σ2). Basically, when rates of evolution are high, we should see large independent contrasts in that part of the tree (Garland 1992).

In his original description of this approach, Garland (1992) proposed using a statistical test to compare the absolute value of contrasts between clades (or between a single clade and the rest of the phylogenetic tree). In particular, Garland (1992) suggests using a t-test, as long as the absolute value of independent contrasts are approximately normally distributed. However, under a Brownian motion model, the contrasts themselves – but not the absolute values of the contrasts – should be approximately normal, so it is quite likely that absolute values of contrasts will strongly violate the assumptions of a t-test.

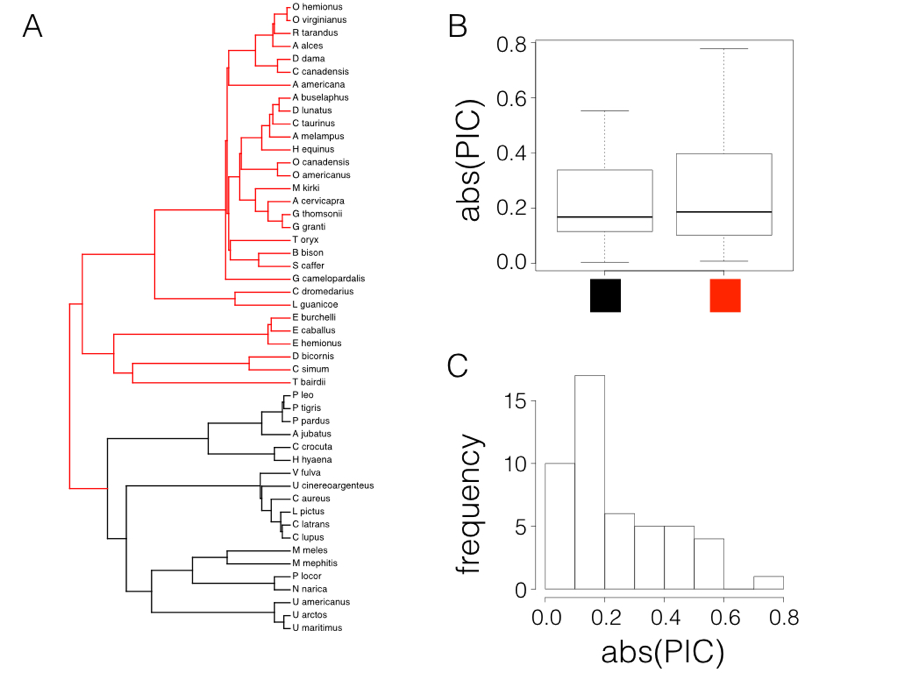

Figure 6.2. Rate tests comparing carnivores (black) with other mammals (red; Panel A) using data from Garland (1992). Box-plots show only a slight difference in the absolute value of independent contrasts for the two clades, and the distribution of absolute values of contrasts is strongly skewed. Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

In fact, if we try this test on mammal body size, contrasting the two major clades in the tree (carnivores versus non-carnivores, Figure 6.2A), there looks to be a small difference in the absolute value of contrasts (Figure 6.2B). A t-test is not significant (Welch two-sample t-test P = 0.42), but we also can see that the distribution of PIC absolute values is strongly skewed (Figure 6.2C).

There are other simple options that might work better in general. For example, one could also compare the magnitudes of the squared contrasts, although these are also not expected to follow a normal distribution. Alternatively, we can again follow Garland’s (1992) suggestion and use a Mann-Whitney U-test, the nonparametric equivalent of a t-test, on the absolute values of the contrasts. Since Mann-Whitney U tests use ranks instead of values, this approach will not be sensitive to the fact that the absolute values of contrasts are not normal. If the P-value is significant for this test then we have evidence that the rate of evolution is greater in one part of the tree than another.

In the case of mammals, a Mann-Whitney U test also shows no significant differences in rates of evolution between carnivores and other mammals (W = 251, P = 0.70).

Section 6.3b: Rate tests using maximum likelihood and AIC

One can also carry out rate comparisons using a model-selection framework (O’Meara et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2006). To do this, we can fit single- and multiple-rate Brownian motion models to a phylogenetic tree, then compare them using a model selection method like AICc. For example, in the example above, we tested whether or not one subclade in the mammal tree (carnivores) has a very different rate of body size evolution than the rest of the clade. We can use an ML-based model selection method to compare the fit of a single-rate model to a model where the evolutionary rate in carnivores is different from the rest of the clade, and use this test evaluate the support for that hypothesis.

This test requires the likelihood for a multi-rate Brownian motion model on a phylogenetic tree. We can derive such an equation following the approach presented in Chapter 4. Recall that the likelihood equations for (constant-rate) Brownian motion use a phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix, C, that is based on the branch lengths and topology of the tree. For single-rate Brownian motion, the elements in C are derived from the branch lengths in the tree. Traits are drawn from a multivariate normal distribution with variance-covariance matrix:

(Equation 6.5)

VH1 = σ2Ctree

One simple way to fit a multi-rate Brownian motion model is to construct separate C matrices, one for each rate category in the tree. For example, imagine that most of a clade evolves under a Brownian motion model with rate σ12, but one clade in the tree evolves at a different (higher or lower) rate, σ22. One can construct two C matrices: the first matrix, C1, includes branches that evolve under rate σ12, while the second, C2, includes only branches that evolve under rate σ22. Since all branches in the tree are included in one of these two categories, it will be true that Ctree = C1 + C2. For any particular values of these two rates, traits are drawn from a multivariate normal distribution with variance-covariance matrix:

(Equation 6.6)

VH2 = σ12C1 + σ22C2

We can now treat this as a model comparison-problem, contrasting H1: traits on the tree evolved under a constant-rate Brownian motion model, with H2: traits on the tree evolved under a multi-rate Brownian motion model. Note that H1 is a special case of H2 when σ12 = σ22; that is, these two models are nested and can be compared using a likelihood ratio test. Of course, one can also compare the two models using AICc.

For the mammal body size example, you might recall our ML single-rate Brownian motion model (σ2 = 0.088, $\bar{z}(0) = 4.64$, lnL = −78.0, AICc = 160.4). We can compare that to the fit of a model where carnivores get their own rate parameter (σc2) that might differ from that of the rest of the tree (σo2). Fitting that model, we find the following maximum likelihood parameter estimates: $\hat{\sigma}_c^2 = 0.068$, $\hat{\sigma}_o^2 = 0.01$, $\hat{\bar{z}}(0) = 4.51$). Carnivores do appear to be evolving more rapidly. However, the fit of this model is not substantially better than the single-rate Brownian motion (lnL = −77.6, AICc = 162.3).

There is one complication, which is how to deal with the actual branch along which the rate shift is thought to have occurred. O’Meara et al. (2006) describe “censored” and “noncensored” versions of their test, which differ in whether or not branches where rate shifts actually occur are included in the calculation. In the censored version of the test, O’Meara et al. (2006) omit the branch where we think a shift occurred, while in the noncensored version O’Meara et al. (2006) include that branch in one of the two rate categories (this is what I did in the example above, adding the stem branch of carnivores in the “non-carnivore” category). One could also specify where, exactly, the rate shift occurred along the branch in question, placing part of the branch in each of the two rate categories as appropriate. However, since we typically have little information about what happened on particular branches in a phylogenetic tree, results from these two approaches are not very different – unless, as stated by O’Meara et al. (2006), unusual evolutionary processes have occurred on the branch in question.

A similar approach was described by Thomas et al. (2006) but considers differences across clades to include changes in any of the two parameters of a Brownian motion model (σ2, $\bar{z}(0)$, or both). Remember that $\bar{z}(0)$ is the expected mean of species within a clade under a Brownian motion, but also represents the starting value of the trait at time zero. Allowing $\bar{z}(0)$ to vary across clades effectively allows different clades to have different “starting points” in phenotype space. In the case of comparing a monophyletic subclade to the rest of a tree, Thomas et al.’s (2006) approach is equivalent to the “censored” test described above. However, one drawback to both the Thomas et al. (2006) approach and the “censored” test is that, because clades each have their own mean, we no longer can tie the model that we fit using likelihood to any particular evolutionary process. Mathematically, changing $\bar{z}(0)$ in a subclade postulates that the trait value changed somehow along the branch leading to that clade, but we do not specify the way that the trait changed – the change could have been gradual or instantaneous, and no amount or pattern of change is more or less likely than anything else. Of course, one can describe evolutionary scenarios that might act like this process - but we begin to lose any potential tie to explicit evolutionary processes.

Section 6.3c: Rate tests using Bayesian MCMC

It is also possible to carry out this test in a Bayesian MCMC framework. The simplest way to do that would be to fit model H2 above, that traits on the tree evolved under a multi-rate Brownian motion model, in a Bayesian framework. We can then specify prior distributions and sample the three model parameters ($\bar{z}(0)$, σ12, and σ22) through our MCMC. At the end of our analysis, we will have posterior distributions for the three model parameters. We can test whether rates differ among clades by calculating a posterior distribution for the composite parameter σdiff2 = σ12 − σ22. The proportion of the posterior distribution for σdiff2 that is positive or negative gives the posterior probability that σ12 is greater or less than σ22, respectively.

Perhaps, though, researchers are unsure of where, exactly, the rate shift might have occurred, and want to incorporate some uncertainty in their analysis. In some cases, rate shifts are thought to be associated with some other discrete character, such as living on land (state 0) or in the water (1). In such cases, one way to proceed is to use stochastic character mapping (see Chapter 8) to map state changes for the discrete character on the tree, and then run an analysis where rates of evolution of the continuous character of interest depend on the mapping of our discrete states. This protocol is described most fully by Revell (2013), who also points out that rate estimates are biased to be more similar when the discrete character evolves quickly.

It is even possible to explore variation in Brownian rates without invoking particular a priori hypotheses about where the rates might change along branches in a tree. These methods rely on reversible-jump MCMC, a Bayesian statistical technique that allows one to consider a large number of models, all with different numbers of parameters, in a single Bayesian analysis. In this case, we consider models where each branch in the tree can potentially have its own Brownian rate parameter. By constraining sets of these rate parameters to be equal to one another, we can specify a huge number of models for rate variation across trees. The reversible-jump machinery, which is beyond the scope of this book, allows us to generate a posterior distribution that spans this large set of models where rates vary along branches in a phylogenetic tree (see Eastman et al. 2011 for details).

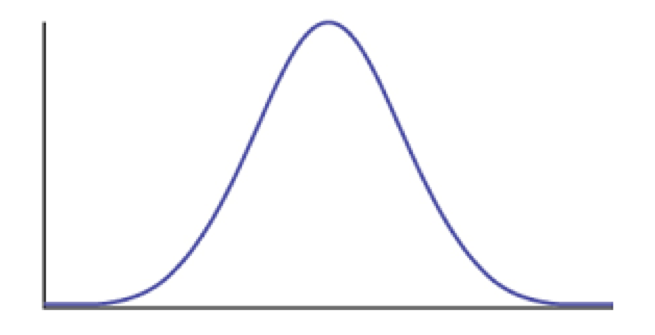

Section 6.4: Non-Brownian evolution under stabilizing selection

We can also consider the case where a trait evolves under the influence of stabilizing selection. Assume that a trait has some optimal value, and that when the population mean differs from the optimum the population will experience selection towards the optimum (Figure 6.3). As I will show below, when traits evolve under stabilizing selection with a constant optimum, the pattern of traits through time can be described using an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) model. It is worth mentioning, though, that this is only one (of many!) models that follow an OU process over long time scales. In other words, even though this model can be described by OU, we cannot make inferences the other direction and claim that OU means that our population is under constant stabilizing selection. In fact, we will see later that we can almost always rule this simple version of the OU model out over long time scales by looking at the actual parameter values of the model compared to what we know about species’ population sizes and trait heritabilities.

Figure 6.3. Plot of species trait (x axis) versus fitness (y axis) showing a hypothetical landscape that would produce stabilizing selection. Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

We can follow the modeling approach from chapter 3 to derive the expected distribution of species’ traits on a tree under stabilizing selection. The derivation is a bit long and complicated, so I have moved it to an appendix of this chapter. For now, all you need to know is that we can write down the likelihood of an OU model on a phylogenetic tree (see equation 6.58-6.60, below).

We can fit an OU model to data in a similar way to how we fit BM models in the previous chapters. For any given parameters ($\bar{z}_0$, σ2, α, and θ) and a phylogenetic tree with branch lengths, one can calculate an expected vector of species means and a species variance-covariance matrix. One then uses the likelihood equation for a multivariate normal distribution to calculate the likelihood of this model. This likelihood can then be used for parameter estimation in either a ML or a Bayesian framework.

We can illustrate how this works by fitting an OU model to the mammal body size data that we have been discussing. Using ML, we obtain parameter estimates $\hat{\bar{z}}_0 = 4.60$, $\hat{\sigma}^2 = 0.10$, $\hat{\alpha} = 0.0082$, and $\hat{\theta} = 4.60$. This model has a lnL of -77.6, a little higher than BM, but an AICc score of 161.2, worse than BM. We still prefer Brownian motion for these data. Over many datasets, though, OU models fit better than Brownian motion (see Harmon et al. 2010; Pennell and Harmon 2013).

Section 6.6: Early burst models

Adaptive radiations are a slippery idea. Many definitions have been proposed, some of which contradict one another (reviewed in Yoder et al. 2010). Despite some core disagreement about the concept of adaptive radiations, many discussions of the phenomenon center around the idea of “ecological opportunity.” Perhaps adaptive radiations begin when lineages gain access to some previously unexploited area of niche space. These lineages begin diversifying rapidly, forming many and varied new species. At some point, though, one would expect that the ecological opportunity would be “used up,” so that species would go back to diversifying at their normal, background rates (Yoder et al. 2010). These ideas connect to Simpson’s description of evolution in adaptive zones. According to Simpson (1945), species enter new adaptive zones in one of three ways: dispersal to a new area, extinction of competitors, or the evolution of a new trait or set of traits that allow them to interact with the environment in a new way.

One idea, then, is that we could detect the presence of adaptive radiations by looking for bursts of trait evolution deep in the tree. If we can identify clades, like Darwin’s finches, for example, that might be adaptive radiations, we should be able to uncover this “early burst” pattern of trait evolution.

The simplest way to model an early burst of evolution in a continuous trait is to use a time-varying Brownian motion model. Imagine that species in a clade evolved under a Brownian motion model, but one where the Brownian rate parameter (σ2) slowed through time. In particular, we can follow Harmon et al. (2010) and define the rate parameter as a function of time, as:

(Equation 6.7)

σ2(t)=σ02ebt

We describe the rate of decay of the rate using the parameter b, which must be negative to fit our idea of adaptive radiations. The rate of evolution will slow through time, and will decay more quickly if the absolute value of b is large.

This model also generates a multivariate normal distribution of tip values. Harmon et al. (2010) followed Blomberg's "ACDC" model (2003) to write equations for the means and variances of tips on a tree under this model, which are:

(Equations 6.8-10)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mu_i(t) = \bar{z}_0 \\

V_i(t) = \sigma_0^2 \frac{e^{b T_i}-1}{b}

V_{ij}(t) = \sigma_0^2 \frac{e^{b s_{ij}}-1}{b}

\end{array}

$$

Again, we can generate a vector of means and a variance-covariance matrix for this model given parameter values ($\bar{z}_0$, σ2, and b) and a phylogenetic tree. We can then use the multivariate normal probability distribution function to calculate a likelihood, which we can then use in a ML or Bayesian statistical framework.

For mammal body size, the early burst model does not explain patterns of body size evolution, at least for the data considered here ($\hat{\bar{z}}_0 = 4.64$, $\hat{\sigma}^2 = 0.088$, $\hat{b} = -0.000001$, lnL = −78.0, AICc = 162.6).

Section 6.7: Peak shift models

A second model considered by Hansen and Martins (1996) describes the circumstance where traits change in a punctuated manner. One can imagine a scenario where species evolve on an adaptive landscape with many peaks; usually, populations stay on a single peak and phenotypes do not change, but occasionally a population will transition from one peak to another. We can either assume that these changes occur at random times, defining an average interval between peak shifts, or we can associate shifts with other traits that we map on the phylogenetic tree (for example, major geographic dispersal or vicariance events, or the evolution of certain traits).

We have developed peak shift models by integrating OU models and reversible-jump MCMC (Uyeda and Harmon 2014). The mathematics of this model are beyond the scope of this book, but follow closely from the description of the multi-rate Brownian motion model described in the section “variation in rates of trait evolution across clades,” above. In this case, when we change model parameters, we move among OU regimes, and can alter the OU model parameters σ2 or α. The approach can be used to either identify parts of the tree that are evolving in separate regimes or to test particular hypotheses about the drivers of evolution.

Section 6.8: Summary

In this chapter, I have described a few models that represent alternatives to Brownian motion, which is still the dominant model of trait evolution used in the literature. These examples really represent the beginnings of a whole set of models that one might fit to biological data. The best applications of this type of approach, I think, are in testing particular biologically motivated hypotheses using comparative data.

Section 6.9: Footnotes

1: Pagel's original models were initially focused on discrete characters, but - as he later pointed out - apply equally well to continuous characters.

Section 6.10: Appendix: Deriving an OU model under stabilizing selection

We can first consider the evolution of the trait on the “stem” branch, before the divergence of species A and B. We model stabilizing selection with a single optimal trait value, located at θ. An example of such a surface is plotted as Figure 6.3. We can describe fitness of an individual with phenotype z as:

(Equation 6.11)

W = e−γ(z − θ)2

We have introduced a new variable, γ, which captures the curvature of the selection surface. To simplify the calculations, we will assume that stabilizing selection is weak, so that γ is small.

We can use a Taylor expansion of this function to approximate equation 6.7 using a polynomial. Our assumption that γ is small means that we can ignore terms of order higher than γ2:

(Equation 6.12)

W = 1 − γ(z − θ)2

This makes good sense, since a quadratic equation is a good approximation of the shape of a normal distribution near its peak. The mean fitness in the population is then:

(Equation 6.13)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\bar{W} = E[W] = E[1 - \gamma (z - \theta)^2] \\

= E[1 - \gamma (z^2 - 2 z \theta + \theta^2)] \\

= 1 - \gamma (E[z^2] - E[2 z \theta] + E[\theta^2]) \\

= 1 - \gamma (\bar{z}^2 - V_z - 2 \bar{z} \theta + \theta ^2) \\

\end{array}

$$

We can find the rate of change of fitness with respect to changes in the trait mean by taking the derivative of (6.9) with respect to $\bar{z}$:

(Equation 6.14)

$$

\frac{\partial \bar{W}}{\partial \bar{z}} = -2 \gamma \bar{z} + 2 \gamma \theta = 2 \gamma (\theta - \bar{z})

$$

We can now use Lande’s (1976) equation for the dynamics of the population mean through time for a trait under selection:

(Equation 6.15)

$$

\Delta \bar{z} = \frac{G}{\bar{W}} \frac{\partial \bar{W}}{\partial \bar{z}}

$$

Substituting equations 6.9 and 6.10 into equation 6.11, we have:

(Equation 6.16)

$$

\Delta \bar{z} = \frac{G}{\bar{W}} \frac{\partial \bar{W}}{\partial \bar{z}} = \frac{G}{1 - \gamma (\bar{z}^2 - V_z - 2 \bar{z} \theta + \theta ^2)} 2 \gamma (\theta - \bar{z})

$$

Then, simplifying further with another Taylor expansion, we obtain:

(Equation 6.17)

$$

\bar{z}' = \bar{z} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{z}) + \delta

$$

Here, $\bar{z}$ is the species’ trait value in the previous generation and $\bar{z}'$ in the next, while G is the additive genetic variance in the population, γ the curvature of the selection surface, θ the optimal trait value, and δ a random component capturing the effect of genetic drift. We can find the expected mean of the trait over time by taking the expectation of this equation:

(Equation 6.18)

$$

E[\bar{z}'] = \mu_z' = \mu_z + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \mu_z)

$$

We can then solve this differential equations given the starting condition $\mu_z(0) = \bar{z}(0)$. Doing so, we obtain:

(Equation 6.19)

$$

\mu_z(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G t \gamma} (\bar{z}(0)-\theta)

$$

We can take a similar approach to calculate the expected variance of trait values across replicates. We use a standard expression for variance:

(Equations 6.20-22)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_z' = E[\bar{z}'^2] + E[\bar{z}']^2 \\

V_z' = E[(\bar{z} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{z}) + \delta)^2] - E[\bar{z} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{z}) + \delta]^2 \\

V_z' = G/n + (1 - 2 G \gamma)^2 V_z \\

\end{array}

$$

If we assume that stabilizing selection is weak, we can simplify the above expression using a Taylor series expansion:

(Equation 6.23)

$$

V_z' = G/n + (1 - 4 G \gamma) V_z \\

$$

We can then solve this differential equation with starting point Vz(0)=0:

(Equation 6.24)

$$

V_z(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G t \gamma}-1}{4 n \gamma}

$$

Equations 6.15 and 6.20 are equivalent to a standard stochastic model for constrained random walks called an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. Typical Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes have four parameters: the starting value ($\bar{z}(0)$), the optimum (θ), the drift parameter (σ2), and a parameter describing the strength of constraints (α). In our parameterization, $\bar{z}(0)$ and θ are as given, α = 2G, and σ2 = G/n.

We now need to know how OU models behave when considered along the branches of a phylogenetic tree. In the simplest case, we can describe the joint distribution of two species, A and B, descended from a common ancestor, z. Using equation 6.17, expressions for trait values of species A and B are:

(Equations 6.25-26)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\bar{a}' = \bar{a} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta \\

\bar{b}' = \bar{b} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{b}) + \delta \\

\end{array}

$$

Expected values of these two equations give equations for the means, using equation 6.19:

(Equations 6.27-28)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mu_a' = \mu_a + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \mu_a) \\

\mu_b' = \mu_b + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \mu_b) \\

\end{array}

$$

We can solve this system of differential equations, given starting conditions $\mu_a(0)=\bar{a}_0$ and $\mu_b(0)=\bar{b}_0$:

(Equations 6.29-30)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mu_a'(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G t \gamma} (\bar{a}_0 - \theta) \\

\mu_b'(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G t \gamma} (\bar{b}_0 - \theta) \\

\end{array}

$$

However, we can also note that the starting value for both a and b is the same as the ending value for species z on the root branch of the tree. If we denote the length of that branch as t1 then:

(Equation 6.31)

$$

E[\bar{a}_0] = E[\bar{b}_0] = E[\bar{z}(t_1)] = e^{-2 G t_1 \gamma} (\bar{z}_0 - \theta)

$$

Substituting this into equations (6.25-26):

(Equations 6.32-33)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mu_a'(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G \gamma (t_1 + t)} (\bar{z}_0 - \theta) \\

\mu_b'(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G \gamma (t_1 + t)} (\bar{z}_0 - \theta) \\

\end{array}

$$

Equations

We can calculate the expected variance across replicates of species A and B, as above:

(Equations 6.34-36)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_a' = E[\bar{a}'^2] + E[\bar{a}']^2 \\

V_a' = E[(\bar{a} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta)^2] + E[\bar{a} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta]^2 \\

V_a' = G / n + (1 - 2 G \gamma)^2 V_a \\

\end{array}

$$

Similarly,

(Equations 6.37-38)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_b' = E[\bar{b}'^2] + E[\bar{b}']^2 \\

V_b' = G / n + (1 - 2 G \gamma)^2 V_b \\

\end{array}

$$

Again we can assume that stabilizing selection is weak, and simplify these expressions using a Taylor series expansion:

(Equations 6.39-40)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_a' = G / n + (1 - 4 G \gamma) V_a \\

V_b' = G / n + (1 - 4 G \gamma) V_b \\

\end{array}

$$

We have a third term to consider, the covariance between species A and B due to their shared ancestry. We can use a standard expression for covariance to set up a third differential equation:

(Equations 6.41-43)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_{ab}' = E[\bar{a}' \bar{b}'] + E[\bar{a}'] E[\bar{b}'] \\

V_{ab}' = E[(\bar{a} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta)(\bar{b} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{b}) + \delta)] + E[\bar{a} \\

+ 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta] E[\bar{a} + 2 G \gamma (\theta - \bar{a}) + \delta] \\

V_{ab}' = V_{ab} (1 - 2 G \gamma)^2

\end{array}

$$

We again use a Taylor series expansion to simplify:

(Equations 6.44)

Vab′= − 4VabGγ

Note that under this model the covariance between A and B decreases through time following their divergence from a common ancestor.

We now have a system of three differential equations. Setting initial conditions Va(0)=Va0, Vb(0)=Vb0, and Vab(0)=Vab0, we solve to obtain:

(Equations 6.45-47)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_a(t) = \frac{1 - e^{-4 G \gamma t}}{4 n \gamma} + V_{a0} \\

V_b(t) = \frac{1 - e^{-4 G \gamma t}}{4 n \gamma} + V_{b0} \\

V_{ab}(t) = V_{ab0} e^{-4 G \gamma t} \\

\end{array}

$$

We can further specify the starting conditions by noting that both the variance of A and B and their covariance have an initial value given by the variance of z at time t1:

(Equations 6.48)

$$

V_{a0} = V_{ab0} = V_{ab0} = V_z(t_1) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma t_1}-1}{4 n \gamma} \\

$$

Substituting 6.44 into 6.41-43, we obtain:

(Equations 6.49-51)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_a(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma (t_1 + t)} -1}{4 n \gamma} \\

V_b(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma (t_1 + t)} -1}{4 n \gamma} \\

V_{ab}(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma t} -e^{-4 G \gamma (t_1 + t)}}{4 n \gamma} \\

\end{array}

$$

Under this model, the trait values follow a multivariate normal distribution; one can calculate that all of the other moments of this distribution are zero. Thus, the set of means, variances, and covariances completely describes the distribution of A and B. Also, as γ goes to zero, the selection surface becomes flatter and flatter. Thus at the limit as γ approaches 0, these equations are equal to those for Brownian motion (see chapter 4).

This quantitative genetic formulation – which follows Lande (1976) – is different from the typical parameterization of the OU model for comparative methods. We can obtain the “normal” OU equations by substituting α = 2Gγ and σ2 = G/n:

(Equations 6.52-54)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

V_a(t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \alpha} (e^{-2 \alpha (t_1 + t)} - 1) \\

V_b(t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \alpha} (e^{-2 \alpha (t_1 + t)} - 1) \\

V_ab(t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \alpha} e^{-2 \alpha t} (1-e^{-2 \alpha t_1}) \\

\end{array}

$$

These equations are mathematically equivalent to the equations in Butler et al. (2004) applied to a phylogenetic tree with two species.

We can easily generalize this approach to a full phylogenetic tree with n taxa. In that case, the n species trait values will all be drawn from a multivariate normal distribution. The mean trait value for species i is then:

(Equation 6.55)

$$

\mu_i(t) = \theta + e^{-2 G \gamma T_i}(\bar{z}_0 - \theta)

$$

Here Ti represents the total branch length separating that species from the root of the tree. The variance of species i is:

(Equation 6.56)

$$

V_i(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma T_i} - 1}{4 n \gamma}

$$

Finally, the covariance between species i and j is:

(Equation 6.57)

$$

V_{ij}(t) = \frac{e^{-4 G \gamma (T_i - s_{ij})}-e^{-4 G \gamma T_i}}{4 n \gamma}

$$

Note that the above equation is only true when Ti = Tj – which is only true for all i and j if the tree is ultrametric. We can substitute the normal OU parameters, α and σ2, into these equations:

(Equations 6.58-60)

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\mu_i(t) = \theta + e^{- \alpha T_i}(\bar{z}_0 - \theta) \\

V_i(t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \alpha} e^{-2 \alpha T_i} - 1 \\

V_{ij}(t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \alpha} (e^{-2 \alpha (T_i - s_{ij})}-e^{-2 \alpha T_i}) \\

\end{array}

$$

References

Alfaro, M. E. 2013. Key evolutionary innovations. in J. B. Losos, D. A. Baum, D. J. Futuyma, H. E. Hoekstra, R. E. Lenski, A. J. Moore, C. L. Peichel, D. Schluter, and M. C. Whitlock, eds. The Princeton guide to evolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Blomberg, S. P., T. Garland Jr, and A. R. Ives. 2003. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: Behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution 57:717–745.

Boettiger, C., G. Coop, and P. Ralph. 2012. Is your phylogeny informative? Measuring the power of comparative methods. Evolution 66:2240–2251.

Bokma, F. 2008. Detection of “punctuated equilibrium” by Bayesian estimation of speciation and extinction rates, ancestral character states, and rates of anagenetic and cladogenetic evolution on a molecular phylogeny. Evolution 62:2718–2726. Blackwell Publishing Inc.

Eastman, J. M., M. E. Alfaro, P. Joyce, A. L. Hipp, and L. J. Harmon. 2011. A novel comparative method for identifying shifts in the rate of character evolution on trees. Evolution 65:3578–3589.

Garland, T., Jr. 1992. Rate tests for phenotypic evolution using phylogenetically independent contrasts. Am. Nat. 140:509–519.

Goldberg, E. E., and B. Igić. 2012. Tempo and mode in plant breeding system evolution. Evolution 66:3701–3709. Wiley Online Library.

Grant, P. R., and B. R. Grant. 2002. Unpredictable evolution in a 30-year study of Darwin’s finches. Science 296:707–711.

Grant, P. R., and R. B. Grant. 2011. How and why species multiply: The radiation of Darwin’s finches. Princeton University Press.

Hansen, T. F., and E. P. Martins. 1996. Translating between microevolutionary process and macroevolutionary patterns: The correlation structure of interspecific data. Evolution 50:1404–1417.

Harmon, L. J., J. B. Losos, T. Jonathan Davies, R. G. Gillespie, J. L. Gittleman, W. Bryan Jennings, K. H. Kozak, M. A. McPeek, F. Moreno-Roark, T. J. Near, and Others. 2010. Early bursts of body size and shape evolution are rare in comparative data. Evolution 64:2385–2396.

Hunter, J. P. 1998. Key innovations and the ecology of macroevolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13:31–36.

Lande, R. 1976. Natural selection and random genetic drift in phenotypic evolution. Evolution 30:314–334.

O’Meara, B. C., C. Ané, M. J. Sanderson, and P. C. Wainwright. 2006. Testing for different rates of continuous trait evolution using likelihood. Evolution 60:922–933.

Pagel, M. 1999a. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 401:877–884.

Pagel, M. 1999b. The maximum likelihood approach to reconstructing ancestral character states of discrete characters on phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 48:612–622.

Pennell, M. W., and L. J. Harmon. 2013. An integrative view of phylogenetic comparative methods: Connections to population genetics, community ecology, and paleobiology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1289:90–105.

Revell, L. J. 2013. Two new graphical methods for mapping trait evolution on phylogenies. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4:754–759.

Revell, L. J., L. J. Harmon, and D. C. Collar. 2008. Phylogenetic signal, evolutionary process, and rate. Syst. Biol. 57:591–601.

Simpson, G. G. 1945. Tempo and mode in evolution. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 8:45–60.

Thomas, G. H., R. P. Freckleton, and T. Székely. 2006. Comparative analyses of the influence of developmental mode on phenotypic diversification rates in shorebirds. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273:1619–1624.

Uyeda, J. C., and L. J. Harmon. 2014. A novel bayesian method for inferring and interpreting the dynamics of adaptive landscapes from phylogenetic comparative data. Syst. Biol. 63:902–918. sysbio.oxfordjournals.org.

Yoder, J. B., E. Clancey, S. Des Roches, J. M. Eastman, L. Gentry, W. Godsoe, T. J. Hagey, D. Jochimsen, B. P. Oswald, J. Robertson, and Others. 2010. Ecological opportunity and the origin of adaptive radiations. J. Evol. Biol. 23:1581–1596. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.