Phylogenetic Comparative Methods learning from trees

- Chapter 13: Characters and diversification rates

- Section 13.1: The evolution of self-incompatibility

- Section 13.2: A State-Dependent Model of Diversification

- Section 13.3: Calculating Likelihoods for State-dependent diversification models

- Section 13.4: ML and Bayesian Tests for State-Dependent Diversification

- Section 13.5: Potential Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Section 13.6: Summary

Chapter 13: Characters and diversification rates

Section 13.1: The evolution of self-incompatibility

Most people have not spent a lot of time thinking about the sex lives of plants. The classic mode of sexual reproduction in angiosperms (flowering plants) involves pollen (the male gametophyte stage of the plant life cycle). Pollen lands on the pistil (the female reproductive structure) and produces a pollen tube. Sperm cells move down the pollen tube, and one sperm cell unites with the egg to form a new zygote in the ovule.

As you might imagine, plants have little control over what pollen grains land on their pistil (although plant species do have some remarkable adaptations to control pollination by animals; see Anders Nilsson 1992). In particular, this "standard" mode of reproduction leaves open the possibility of self-pollination, where pollen from a plant fertilizes eggs from the same plant (Stebbins 1950). Self-fertilization (sometimes called selfing) is a form of asexual reproduction, but one that involves meiosis; as such, there are costs to self-fertilization. The main cost is inbreeding depression, a reduction in offspring fitness associated with recessive deleterious alleles across the genome (Holsinger et al. 1984).

Some species of angiosperms can avoid self-fertilization through self-incompatibility (Bateman 1952). In plants with self-incompatibility, the process by which the sperm meets the egg is interrupted at some stage if pollen grains have a genotype that is the same as the parent (e.g. Schopfer et al. 1999). This prevents selfing – and also prevents sexual reproduction with plants that have the same genotype(s) at loci involved in the process.

Species of angiosperms are about evenly divided between these two states of self-compatibility and self-incompatibility (Igic and Kohn 2006). Furthermore, self-incompatible species are scattered throughout the phylogenetic tree of angiosperms (Igic and Kohn 2006).

The evolution of selfing is a good example of a trait that might have a strong effect on diversification rates by altering speciation, extinction, or both. One can easily imagine, for example, how incompatibility loci might facilitate the evolution of reproductive isolation among populations, and how lineages with such loci might diversify at a very different tempo than those without (Goldberg et al. 2010).

In this chapter, we will learn about a family of models where traits can affect diversification rates. I will also address some of the controversial aspects of these models and how we can improve these approaches in the future.

Section 13.2: A State-Dependent Model of Diversification

The models that we will consider in this chapter include trait evolution and associated lineage diversification. In the simplest case, we can consider a model where the character has two states, 0 and 1, and diversification rates depend on those states.

We need to model the transitions among these states, which we can do in an identical way to what we did in Chapter 7 using a continuous-time Markov model. We express this model using two rate parameters, a forward rate q01 and a backwards rate q10.

We now consider the idea that diversification rates might depend on the character state. We assume that species with character state 0 have a certain speciation rate (λ0) and extinction rate (μ0), and that species in 1 have potentially different rates of both speciation (λ1) and extinction (μ1). That is, when the character evolves, it affects the rate of speciation and/or extinction of the lineages. Thus, we have a six-parameter model (Maddison et al. 2007). We assume that parent lineages give birth to daughters with the same character state, that is that character states do not change at speciation.

It is straightforward to simulate evolution under our state-dependent model of diversification. We proceed in the same way as we did for birth-death models, by drawing waiting times, but these waiting times can be waiting times to the next character state change, speciation, or extinction event. In particular, imagine that there are n lineages present at time t, and that k of these lineages are in state 0 (and n − k are in state 1). The waiting time to the next event will follow an exponential distribution with a rate parameter of:

(eq. 13.1)

ρ = k(q01 + λ0 + μ0)+(n − k)(q10 + λ1 + μ1)

This equation says that the total rate of events is the sum of the events that can happen to lineages with state 0 (state change to 1, speciation, or extinction) and the analogous events that can happen to lineages with state 1. Once we have a waiting time, we can assign an event type depending on probabilities. For example, the probability that the event is a character state change from 0 to 1 is:

(eq. 13.2)

pq01 = (n ⋅ q01)/ρ

And the probability that the event is the extinction of a lineage with character state 1 is:

(eq. 13.3)

pμ1 = [(n − k)⋅μ1]/ρ

And so on for the other four possible events.

Once we have picked an event in this way, we can randomly assign it to one of the lineages in the appropriate state, with each lineage equally likely to be chosen. We then proceed forwards in time until we have a dataset with the desired size or total time depth.

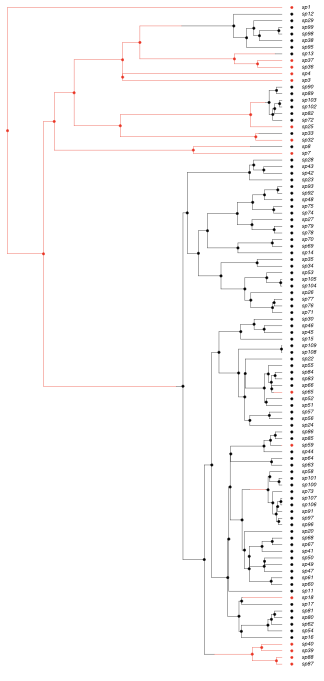

An example simulation is shown in Figure 13.1. As you can see, under these model parameters the impact of character states on diversification is readily apparent. In the next section we will figure out how to extract that information from our data.

Figure 13.1. Simulation of character-dependent diversification. Data were simulated under a model where diversification rate of state zero (red) is substantially lower than that of state 1 (black; model parameters q01 = 110 = 0.05, λ0 = 0.2, λ1 = 0.8, μ0 = μ1 = 0.05). Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

Section 13.3: Calculating Likelihoods for State-dependent diversification models

To calculate likelihoods for state-dependent diversification models we use a pruning algorithm with calculations that progress back through the tree from the tips to the root. We will follow the description of this algorithm in Maddison et al. (2007). We have already used this approach to derive likelihoods for constant rate birth-death models on trees (Chapter 12), and this derivation is similar.

We consider a phylogenetic tree with data on the character states at the tips. For the purposes of this example, we will assume that the tree is complete and correct – we are not missing any species, and there is no phylogenetic uncertainty. We will come back to these two assumptions later in the chapter.

We need to obtain the probability of obtaining the data given the model (the likelihood). As we have seen before, we will calculate that likelihood going backwards in time using a pruning algorithm (Maddison et al. 2007). The key principle, again, is that if we know the probabilities at some point in time on the tree, we can calculate those probabilities at some time point immediately before. By applying this method successively, we can move back towards the root of the tree. We move backwards along each branch in the tree, merging these calculations at nodes. When we get to the root, we have the probability of the data given the model and the entire tree – that is, we have the likelihood.

The other essential piece is that we have a starting point. When we start at the tips of the tree, we assume that our character states are fixed and known. We use the fact that we know all of the species and their character states at the present day as our starting point, and move backwards from there (Maddison et al. 2007). For example, for a species with character state 0, the likelihood for state 0 is 1, and for state 1 is zero. In other words, at the tips of the tree we can start our calculations with a probability of 1 for the state that matches the tip state, and 0 otherwise.

This discussion also highlights the fact that incorporating uncertainty and/or variation in tip states for these algorithms is not computationally difficult – we just need to start from a different point at the tips. For example, if we are completely unsure about the tip state for a certain taxa, we can begin with likelihoods of 0.5 for starting in state 0 and 0.5 for starting in state 1. However, such calculations are not commonly implemented in comparative methods software.

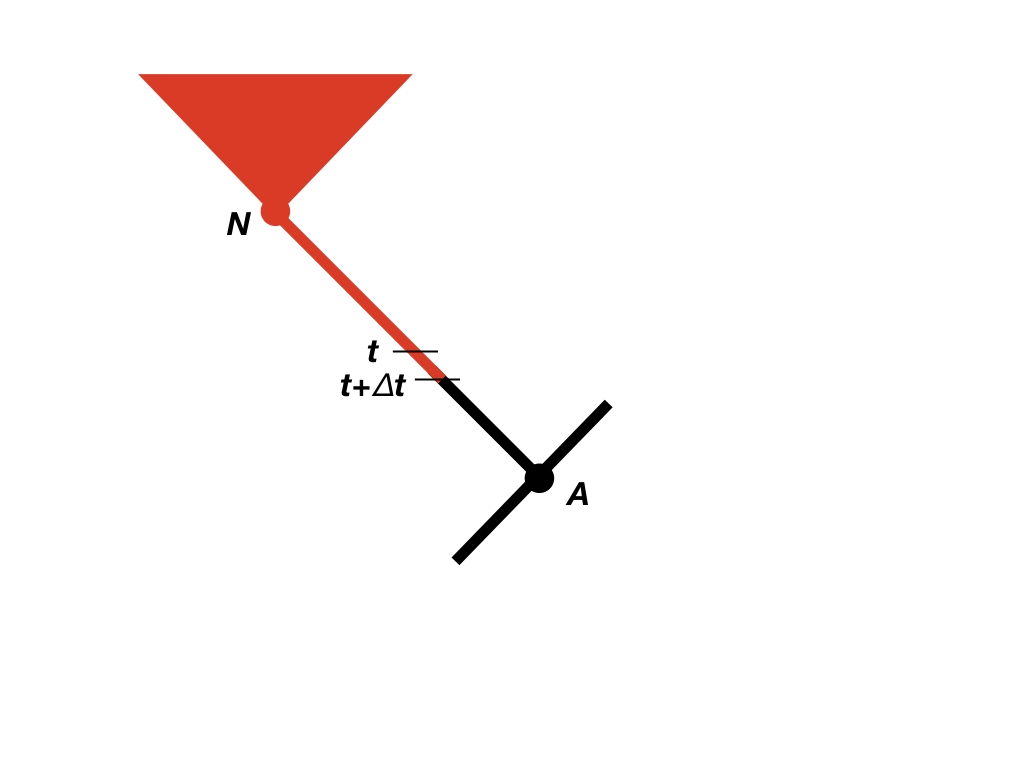

We now need to consider the change in the likelihood as we step backwards through time in the tree (Maddison et al. 2007). We will consider some very small time interval Δt, and later use differential equations to find out what happens in the limit as this interval goes to zero (Figure 13.2). Since we will eventually take the limit as Δt → 0, we can assume that the time interval is so small that, at most, one event (speciation, extinction, or character change) has happened in that interval, but never more than one. We will calculate the probability of the observed data given that the character is in each state at time t, again measuring time backwards from the present day. In other words, we are considering the probability of the observed data if, at time t, the character state were in state 0 [p0(t)] or state 1 [p1(t)]. For now, we can assume we know these probabilities, and try to calculate updated probabilities at some earlier time t + Δt: p0(t + Δt) and p1(t + Δt).

Figure 13.2. Illustration of calculations of probabilities of part of the data descended from node N (red) moving along a branch in the tree. Starting with values for the probability at time t, we calculate the probability at time t + Δt, moving towards the root of the tree. Redrawn from Maddison et al. (2007). Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

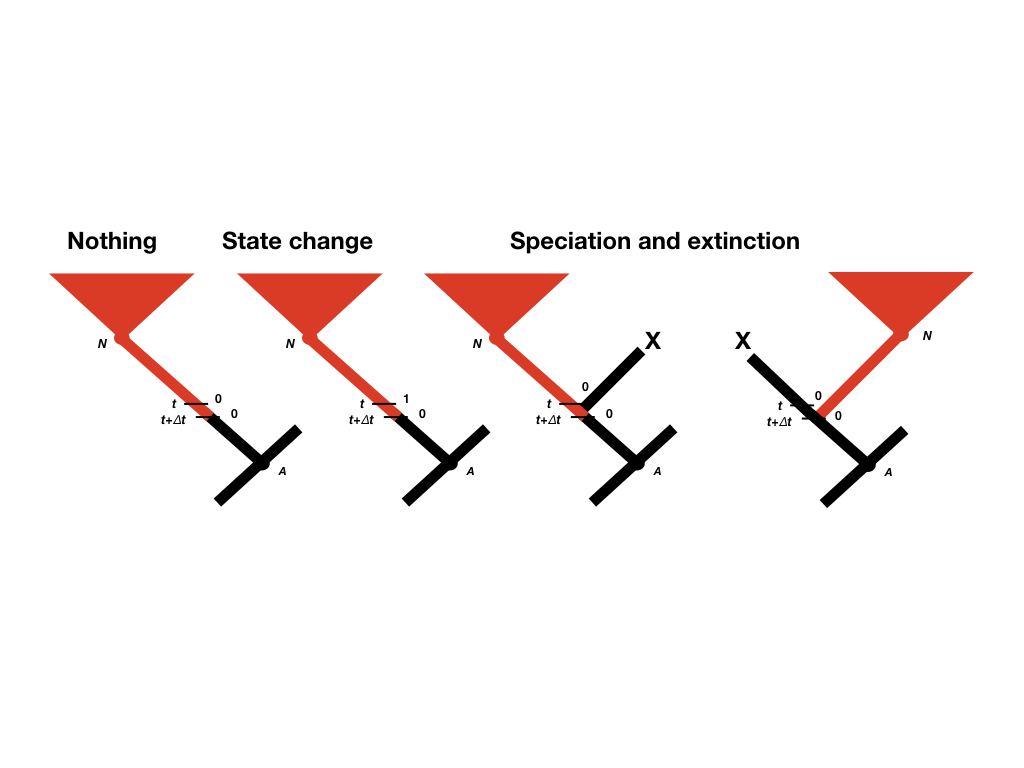

To calculate p0(t + Δt) and p1(t + Δt), we consider all of the possible things that could happen in a time interval Δt along a branch in a phylogenetic tree that are compatible with our dataset (Figure 13.2; Maddison et al. 2007). First, nothing at all could have happened; second, our character state could have changed; and third, there could have been a speciation event. This last event might seem incorrect, as we are only considering changes along branches in the tree and not at nodes. If we did not reconstruct any speciation events at some point along a branch, then how could one have taken place? The answer is that a speciation event could have occurred but all taxa descended from that branch have since gone extinct. We must also consider the possibility that either the right or the left lineage went extinct following the speciation event; that is why the speciation event probabilities appear twice in Figure 13.2 (Maddison et al. 2007).

Figure 13.3. The four scenarios under which a lineage with state 0 at time t + Δt can yield the data descended from node N. Redrawn from Maddison et al. (2007). Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

We can write an equation for these updated probabilities. We will consider the probability that the character is in state 0 at time t + Δt; the equation for state 1 is similar (Maddison et al. 2007).

(eq. 13.4)

$$

\begin{aligned}

p_0 (t+\Delta t)=(1-\mu_0 )\Delta t \cdot [(1-q_{01} \Delta t)(1-\lambda_0 \Delta t) p_0 (t)+q_{01} \Delta t(1-\lambda_0 \Delta t) \\

p_1 (t)+2 \cdot (1-q_{01} \Delta t) \lambda_0 \Delta t \cdot E_0 (t) p_0 (t)]

\end{aligned}

$$

We can multiply through and simplify. We will also drop any terms that include [Δt]2, which become vanishingly small as Δt decreases. Doing that, we obtain (Maddison et al. 2007):

(eq. 13.5)

p0(t + Δt)=[1 − (λ0 + μ0 + q01)Δt]p0(t)+(q01Δt)p1(t)+2(λ0Δt)E0(t)p0(t)

Similarly,

(eq. 13.6)

p1(t + Δt)=[1 − (λ1 + μ1 + q10)Δt]p1(t)+(q10Δt)p0(t)+2(λ1Δt)E1(t)p1(t)

We can then find the instantaneous rate of change for these two equations by solving for p1(t + Δt)/[Δt], then taking the limit as Δt → 0. This gives (Maddison et al. 2007):

(eq. 13.7)

$$

\frac{dp_0}{dt} = -(\lambda_0 + \mu_0 + q_{01}) p_0(t) + q{01}p_1(t) + 2 \lambda_0 E_0(t) p_0(t)

$$

and:

(eq. 13.8)

$$

\frac{dp_1}{dt} = -(\lambda_1 + \mu_1 + q_{10}) p_1(t) + q{10}p_1(t) + 2 \lambda_1 E_1(t) p_1(t)

$$

We also need to consider E0(t) and E1(t). These represent the probability that a lineage with state 0 or 1, respectively, and alive at time t will go extinct before the present day. Neglecting the derivation of these formulas, which can be found in Maddison et al. (2007) and is closely related to similar terms in Chapters 11 and 12, we have:

(eq. 13.9)

$$

\frac{dE_0}{dt} = \mu_0-(\lambda_0+\mu_0+q_{01} ) E_0 (t)+q_{01} E_1 (t)+\lambda_0 [E_0 (t)]^2

$$

and:

(eq. 13.10)

$$

\frac{dE_1}{dt} = \mu_1-(\lambda_1+\mu_1+q_{10} ) E_1 (t)+q_{10} E_0 (t)+\lambda_1 [E_1 (t)]^2

$$

Along a single branch in a tree, we can sum together many such small time intervals. But what happens when we get to a node? Well, if we consider the time interval that contains the node, then we already know what happened – a speciation event. We also know that the two daughters immediately after the speciation event were identical in their traits (this is an assumption of the model). So we can calculate the likelihood for their ancestor for each state as the product of the likelihoods of the two daughter branches coming into that node and the speciation rate (Maddison et al. 2007). In this way, we merge our likelihood calculations along each branch when we get to nodes in the tree.

When we get to the root of the tree, we are almost done – but not quite! We have partial likelihood calculations for each character state – so we know, for example, the likelihood of the data if we had started with a root state of 0, and also if we had started at 1. To merge these we need to use probabilities of each character state at the root of the tree (Maddison et al. 2007). For example, if we do not know the root state from any outside information, we might consider root probabilities for each state to be equal, 0.5 for state 0 and 0.5 for state 1. We then multiply the likelihood associated with each state with the root probability for that state. Finally, we add these likelihoods together to obtain the full likelihood of the data given the model.

The question of which root probabilities to use for this calculation has been discussed in the literature, and does matter in some applications. Aside from equal probabilities of each state, other options include using outside information to inform prior probabilities on each state (e.g. Hagey et al. 2017), finding the calculated equilibrium frequency of each state under the model (Maddison et al. 2007), or weighting each root state by its likelihood of generating the data, effectively treating the root as a nuisance parameter (FitzJohn et al. 2009).

I have described the situation where we have two character states, but this method generalizes well to multi-state characters (the MuSSE method; FitzJohn 2012). We can describe the evolution of the character in the same way as described for multi-state discrete characters in chapter 9. We then can assign unique diversification rate parameters to each of the k character states: λ0, λ1, …, λk and μ0, μ1, …, μk (FitzJohn 2012). It is worth keeping in mind, though, that it is not too hard to construct a model where parameters are not identifiable and model fitting and estimation become very difficult.

Section 13.4: ML and Bayesian Tests for State-Dependent Diversification

Now that we can calculate the likelihood for state-dependent diversification models, formulating ML and Bayesian tests follows the same pattern we have encountered before. For ML, some comparisons are nested and so you can use likelihood ratio tests. For example, we can compare the full BiSSe model (Maddison et al. 2007), with parameters q01, q10, λ0, λ1, μ0, μ1 with a restricted model with parameters q01, q10, λall, μall. Since the restricted model is a special case of the full model where λ0 = λ1 = λall and μ0 = μ1 = μall, we can compare the two using a likelihood ratio test, as described earlier in the book. Alternatively, we can compare a series of BiSSe-type models by comparing their AICc scores.

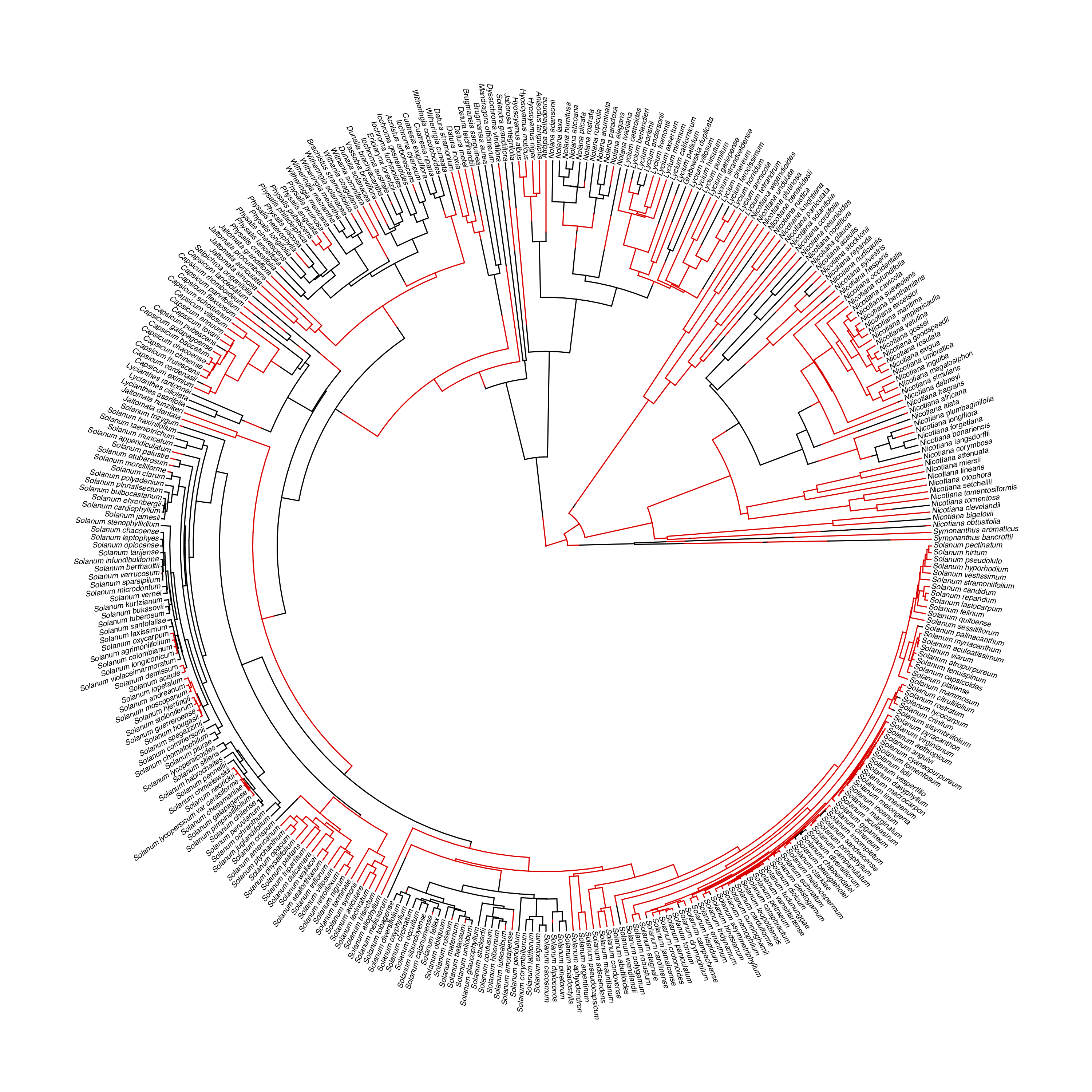

For example, I will apply this approach to the example of self-incompitability. I will use data from Goldberg and Igic (2012), who provide a phylogenetic tree and data for 356 species of Solanaceae. All species were classified as having any form of self incompatibility, even if the state is variable among populations. The data, along with a stochastic character map of state changes, are shown in Figure 13.4.

Figure 13.4. Data from Goldberg and Igic (2012) showing presence (red) and absence (black) of self-incomatibility among Solanaceae. Branches colored using stochastic character mapping under a model with distinct forwards and backwards rates; these reconstructions are biased if characters affect diversification rates. Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

Applying the BiSSe models to these data and assuming that q01 ≠ q10, we obtain the following results:

| Model | Number of parameters | Parameter estimates | lnL | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character-independent model | 4 | λ = 0.65, μ = 0.57 | -945.96 | 1899.9 |

| q01 = 0.16, q10 = 0.09 | ||||

| Speciation rate depends on character | 5 | μ = 0.57 | -945.57 | 1901.1 |

| λ0 = 0.69, λ1 = 0.63 | ||||

| q01 = 0.17, q10 = 0.08 | ||||

| Extinction rate depends on character | 5 | λ = 0.65 | -943.93 | 1897.9 |

| μ0 = 0.45, μ1 = 0.67 | ||||

| q01 = 0.22, q10 = 0.06 | ||||

| Full character-dependent model | 6 | λ0 = 0.49, λ1 = 0.79 | -941.94 | 1895.9 |

| μ0 = 0.20, μ1 = 0.84 | ||||

| q01 = 0.29, q10 = 0.05 |

From this, we conclude that models where the character influences diversification fit best, with the full model receiving the most support. We can't discount the possibility that the character only influences extinction and not speciation, since that model is within 2 AIC units of the best model.

Alternatively, we can carry out a Bayesian test for state-dependent diversification. Like other models in the book, this requires setting up an MCMC algorithm that samples the posterior distributions of our model parameters (FitzJohn 2012). In this case:

- Sample a set of starting parameter values, q01, q10, λ0, λ1, μ0, μ1, from their prior distributions. For example, one could set prior distribution for all parameters as exponential with a mean and variance of λpriori (note that, as usual, the choice for this parameter should depend on the units of tree branch lengths you are using). We then select starting values for all parameters from the prior.

- Given the current parameter values, select new proposed parameter values using the proposal density Q(p′|p). For all parameter values, we can use a uniform proposal density with width wp, so that Q(p′|p) U(p − wp/2, p + wp/2). We can either choose all parameter values simultaneously, or one at a time (the latter is typically more effective).

- Calculate three ratios:

- The prior odds ratio. This is the ratio of the probability of drawing the parameter values p and p′ from the prior. Since we have exponential priors for all parameters, we can calculate this ratio as (eq. 13.11):

$$ R_{prior} = \frac{\lambda_{prior_i} e^{-\lambda_{prior_i} p'}}{\lambda_{prior_i} e^{-\lambda_{prior_i} p}}=e^{\lambda_{prior_i} (p-p')} $$ - The proposal density ratio. This is the ratio of probability of proposals going from p to p′ and the reverse. We have already declared a symmetrical proposal density, so that Q(p′|p)=Q(p|p′) and Rproposal = 1.

- The likelihood ratio. This is the ratio of probabilities of the data given the two different parameter values. We can calculate these probabilities from the approach described in the previous section.

- The prior odds ratio. This is the ratio of the probability of drawing the parameter values p and p′ from the prior. Since we have exponential priors for all parameters, we can calculate this ratio as (eq. 13.11):

- Find Raccept as the product of the prior odds, proposal density ratio, and the likelihood ratio. In this case, the proposal density ratio is 1, so (eq. 13.12):

Raccept = Rprior ⋅ Rlikelihood - Draw a random number u from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. If u < Raccept, accept the proposed value of the parameter(s); otherwise reject, and retain the current value of the two parameters.

- Repeat steps 2-5 a large number of times.

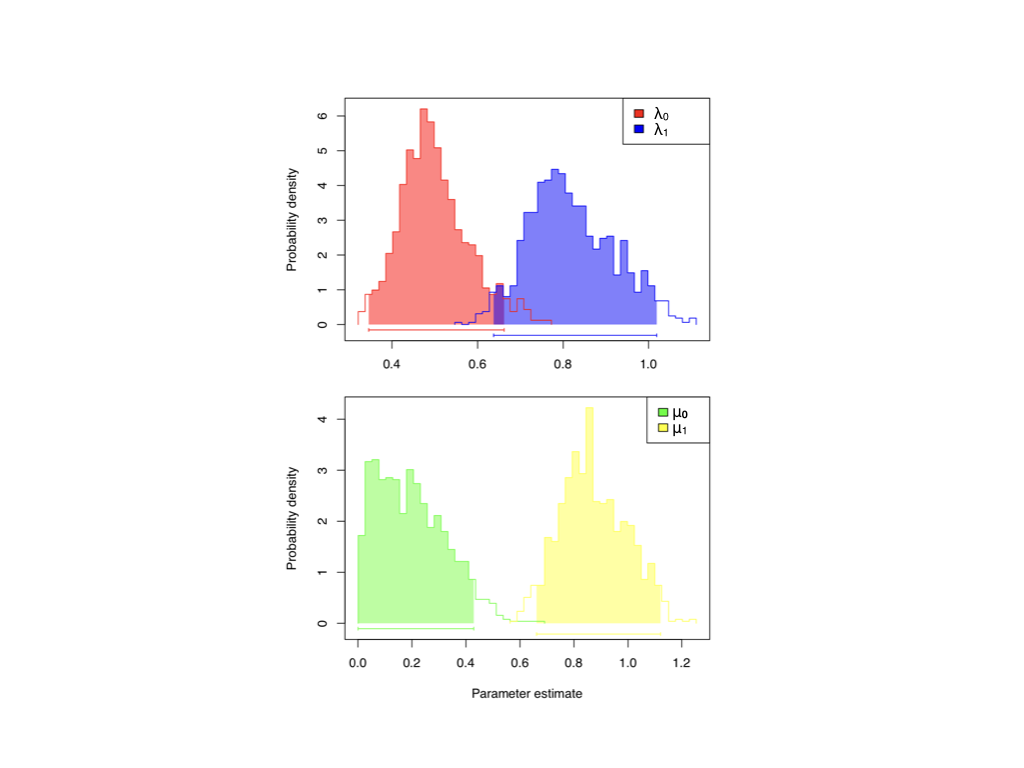

Applying this method to the self-incompatability data, we find that again estimates of speciation and extinction differ substantially among the two character states (Figure 13.5). Since the posterior distributions for extinction do not overlap, we again infer that the character likely influences that model parameter; speciation results are again suggestive but not as conclusive as those for extinction.

Figure 13.5. Bayesian BiSSe analysis of self-incompatibility. Posterior distributions for character-dependent speciation (λ0 and λ1) and extinction (μ0 and μ1). Image by the author, can be reused under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

Section 13.5: Potential Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Recently, a few papers have been published that are critical of state-dependent diversification models (Rabosky and Goldberg 2015, Maddison and FitzJohn (2015)). These papers raise substantive critiques that are important to address when applying the methods described in this chapter to empirical data. In this section I will attempt to describe the critiques and their potential remedies.

The most serious limitation of state-dependent models as currently implemented is that they consider only a relatively small set of possible models. In particular, the approach we describe above compares two models: first, a model where birth and death rates are constant and do not depend on the state of the character; and second, a model where birth and death rates depend only on the character state (Maddison et al. 2007). But there is another possibility that might be (in general) more common than either of the models we consider: birth and death rates vary, but in a way that is not dependent on the particular character we have chosen to analyze. I say that this is probably a common pattern because we know that birth and death rates vary tremendously across lineages in the tree of life (Alfaro et al. 2009), and it seems probable to me that many of our hypotheses about which characters might contribute to that variation are, at this point, stabs in the dark.

This issue is a normal one for statistical analyses – after all, there are always other models outside of our set of considered possibilities. However, in this case, the fact that state-dependent diversification models fail to consider the possibility outlined above causes a very particular – and peculiar – problem: if we apply the tests to empirical phylogenetic trees, even with made-up data, we almost always find statistically significant results (Rabosky and Goldberg 2015). For example, Rabosky and Goldberg (2015) found that there is very often a statistically significant “signal” that the number of letters in a species name is significantly associated with speciation rates across a range of empirical datasets. This result might seem ridiculous and puzzling, as there is no way that species name length should be associated with the diversification processes. However, if we return to our alternative model above, then the results make sense. Rabosky and Goldberg (2015) simulated character evolution on real phylogenetic trees, and their results do not hold when the trees are simulated along with the characters (this is also why Rabosky and Goldberg’s (2015) results do not represent “type I errors,” contra their paper, because the data are not simulated under the null hypothesis). On these real trees, speciation and/or extinction rates vary across clades. Among the two models that the authors consider, both are wrong; speciation and extinction are independent of the character but not constant through time. Of the two alternatives, the state-dependent model tends to fit better because, from a statistical point of view, it is important for the model to capture some variation in birth and death rates across clades. Even a random character will pick up some of this variation, so that the alternative model tends to fit better than the null – even though, in this case, the character has nothing to do with diversification!

Fortunately, there are a number of ways to deal with this problem. First, one can compare the statistical support for the state-dependent model with the support that one obtains for random data. The random data could be simulated on the tree, or one could permute the tips or draw random data from a multinomial distribution (Rabosky and Goldberg 2015). One can then compare, for example, the distribution of ΔAICc scores obtained from these permutations to the ΔAICc for the original data. There are also semi-parametric methods based on permutations that have similar statistical properties (Rabosky and Goldberg 2017). Alternatively, we could explicitly consider the possibility that some unmeasured character is actually the thing that is influencing diversification rates (Beaulieu and O’Meara 2016). This latter approach is the most elegant as we can directly add the model described in this section to our list of candidates (see Beaulieu and O’Meara 2016).

A more general critique of state-dependent models of diversification was raised by Maddison and Fitzjohn (Maddison and FitzJohn 2015). This paper pointed out that statistically significant results for these tests can be driven by an event on a single branch of a tree, and therefore be unreplicated. This is a good criticism that applies equally well to a range of comparative methods. We can deal with this critique, in part, by making sure the events we test are replicated in our data. Together, both of these critiques argue for a stronger set of model adequacy approaches in comparative methods.

Section 13.6: Summary

Many evolutionary models postulate a link between species characteristics and speciation, extinction, or both. These hypotheses can be tested using state-dependent diversification models, which explicitly consider the possibility that species’ characters affect their diversification rates. State-dependent models as currently implemented have some potential problems, but there are methods to deal with these critiques. The overall ability of state-dependent models to explain broad patterns of evolutionary change remains to be determined, but represents a promising avenue for future research.

References

Alfaro, M. E., F. Santini, C. Brock, H. Alamillo, A. Dornburg, D. L. Rabosky, G. Carnevale, and L. J. Harmon. 2009. Nine exceptional radiations plus high turnover explain species diversity in jawed vertebrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:13410–13414. National Acad Sciences.

Anders Nilsson, L. 1992. Orchid pollination biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 7:255–259.

Bateman, A. J. 1952. Self-incompatibility systems in Angiosperms. Heredity 6:285. The Genetical Society of Great Britain.

Beaulieu, J. M., and B. C. O’Meara. 2016. Detecting hidden diversification shifts in models of Trait-Dependent speciation and extinction. Syst. Biol. 65:583–601.

FitzJohn, R. G. 2012. Diversitree: Comparative phylogenetic analyses of diversification in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3:1084–1092.

FitzJohn, R. G., W. P. Maddison, and S. P. Otto. 2009. Estimating trait-dependent speciation and extinction rates from incompletely resolved phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 58:595–611. sysbio.oxfordjournals.org.

Goldberg, E. E., and B. Igić. 2012. Tempo and mode in plant breeding system evolution. Evolution 66:3701–3709. Wiley Online Library.

Goldberg, E. E., J. R. Kohn, R. Lande, K. A. Robertson, S. A. Smith, and B. Igić. 2010. Species selection maintains self-incompatibility. Science 330:493–495.

Hagey, T. J., J. C. Uyeda, K. E. Crandell, J. A. Cheney, K. Autumn, and L. J. Harmon. 2017. Tempo and mode of performance evolution across multiple independent origins of adhesive toe pads in lizards. Evolution 71:2344–2358.

Holsinger, K. E., M. W. Feldman, and F. B. Christiansen. 1984. The evolution of self-fertilization in plants: A population genetic model. Am. Nat. 124:446–453.

Igic, B., and J. R. Kohn. 2006. Bias in the studies of outcrossing rate distributions. Evolution 60:1098–1103.

Maddison, W. P., and R. G. FitzJohn. 2015. The unsolved challenge to phylogenetic correlation tests for categorical characters. Syst. Biol. 64:127–136.

Maddison, W. P., P. E. Midford, S. P. Otto, and T. Oakley. 2007. Estimating a binary character’s effect on speciation and extinction. Syst. Biol. 56:701–710. Oxford University Press.

Rabosky, D. L., and E. E. Goldberg. 2017. FiSSE: A simple nonparametric test for the effects of a binary character on lineage diversification rates. Evolution 71:1432–1442.

Rabosky, D. L., and E. E. Goldberg. 2015. Model inadequacy and mistaken inferences of trait-dependent speciation. Syst. Biol. 64:340–355.

Schopfer, C. R., M. E. Nasrallah, and J. B. Nasrallah. 1999. The male determinant of self-incompatibility in Brassica. Science 286:1697–1700.

Stebbins, G. L. 1950. Variation and evolution in plants. Geoffrey Cumberlege.; London.